The EU’s Proposed PFAS Ban

On February 7, the European Chemicals Agency (ECHA) published their long-awaited proposed restriction of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Prepared by authorities in Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden, the proposal marks the first time that an entire class of substances has been proposed for restriction under REACH.

The restriction proposal itself defines the scope in terms of the chemical substance formula rather than CAS or EC numbers. This was done to prevent “regrettable substitutions.” Since there are (at least) ten thousand different substances that can be classified as PFAS, the development of functional replacements that are similar in structure (and will also result in the problems ECHA is trying to solve) is considered to be a loophole they could not allow.

The proposal will restrict a very wide range of substances and materials that have widespread use in components and materials that are commonplace in electrical and electronic goods, as well as in the manufacturing processes that produce them. Included are these and many others:

- Per the webinar (at 1:34:00 or so), fluoropolymers including PTFE (aka “Teflon®” used in insulation for wiring/cabling for high-frequency signals or nasty environments as well as semiconductor manufacturing piping, among other things) and PVDF (used in lithium-ion batteries)

- PFAS in lubricants

- PFAS in anti-fingerprint coatings on LCD screens for smartphones and other items

- PFAS-based flame retardants in polycarbonates

Many of these substances would no longer be allowed to be used or included in products placed on the market in the EU eighteen months after the proposal is passed and enters into force (EIF). When that is expected is currently unknown, but it is probably at least a year away.

Note that there are proposed derogations that would delay the onset of the restriction to either 6.5 or 13.5 years after the EIF date. Some of these are relevant for specific uses of PFAS in electronics and the electronics supply chain, including 13.5 years for the “semiconductor manufacturing process.”

If you have not already done so, any manufacturer with PFAS in your product or the manufacturing processes for your product must take this very seriously and immediately apply resources to understanding its scope and potential impact to your product line.

On March 22, ECHA opened up a six-month consultation on the proposal. ECHA held a very informative webinar on the topic on April 5, including:

- The REACH restriction process.

- Why PFAS are being restricted.

- Details of the restriction proposal.

- The consultation process and how to participate in an effective manner.

- An informative Q&A session.

Since the restriction documentation provided is nearly 2,000 pages long (!), with a couple important spreadsheets as well, I strongly recommend downloading the presentation material and spending a couple hours to watch this webinar. It will help you understand what you need to be concerned about and direct your research into the extensive documentation. If your application needs a derogation, this is the last chance to make your case before the proposal becomes law.

The EU’s Brominated Flame Retardant (BFR) Strategy

On March 15, ECHA released the Regulatory Strategy for Flame Retardants, identifying aromatic brominated flame retardants (ArBFR – the most common type of BFRs used in electronics applications) as candidates for an EU-wide restriction

The strategy notes that “quite a number of flame retardants are potential candidates for restriction” but indicates that some others are not, while most require more data to define the hazard.

In many cases, BFRs can be replaced with organophosphate-based flame retardants (OPFRs), but it may require a change in material from, for example, ABS to PC/ABS. One potential issue with the use of OPFRs used as a “halogen-free” alternative, in particularly, PC/ABS blends, is, according to the Strategy, that

Fluoropolymers, especially high molecular weight (HMW) PTFE, provide flame retardancy to polymers used in various industrial applications. PTFE, when incorporated into the polymer compound, reduces the dripping of the polymer upon burning and thereby retards the spread of flames. PTFE is added with loadings up to 0,5 wt%.

There are no derogations proposed for this application of PTFE in the PFAS restriction proposal noted above, so it will not be available for this use in the future.

In the conclusion, they indicate that work could soon begin on the ArBFR restriction process. However, for aliphatic BFRs (used in polyurethane foams and unsaturated polyester resins) and OPFRs the recommendation is to wait until the (hazard) data generation process is completed. They expect to “reassess the situation for these groups of flame retardants in 2025 and revise the strategy accordingly.”

One challenge to note here is that any replacement of a BFR with an OPFR should be reviewed against this report and other available information to avoid making a “regrettable substitution” that you will just end up having to replace again should the replacement substance end up being restricted in the future.

Is Anyone Aware that SCCPs are Banned?

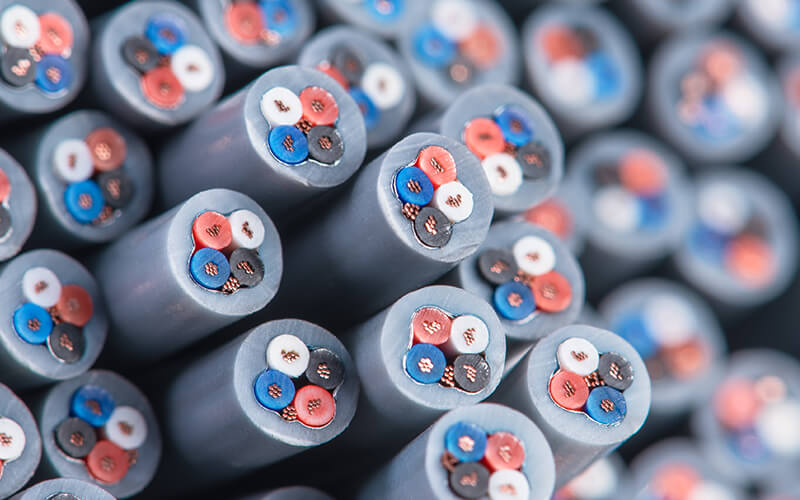

Based on a new scientific study from University of Toronto (and UC Berkeley) researchers, the presence of short-chain chlorinated paraffins (SCCPs), a flame retardant and plasticizer commonly used in polyvinyl chloride (PVC) wire insulation/sheathing and materials is found in over 85 percent of targeted items tested. This includes newly-purchased toys, electronics, clothing and – curiously – paintings.

So, why is this news?

It’s news because the Stockholm Convention banned SCCPs in 2017 (Decision SC-8/11) and, in fact, the Canadian Environmental Protection Act banned them back in 2012. They were listed in Schedule 1 of the Prohibition of Certain Toxic Substances Regulations, 2012 (SOR/2012-285) as “chlorinated alkanes that have the molecular formula CnHxCl(2n+2-x) in which 10 ≤ n ≤ 13” when it was initially published in 2012.

So here it is, 11 years later, and nobody seems to have gotten the message that SCCPs are banned in Canada! Is it just the Canadians, or is this a problem everywhere (we can assume that, since the U.S. never ratified the Stockholm Convention and otherwise has not yet banned SCCPs, they are present in products here)? Well, a quick check of the European Union’s “Safety Gate” (formerly Rapex) system shows over 200 hits in the last eight years. Also banned by the Persistent Organic Pollutants regulation in 2012, this seems to have had little effect on the supply base.

If your products, wiring, cables, etc. are manufactured by a third party, you may want to test for SCCPs and, if found, review the guidance provided to and the extent of your oversight of your supply base. If SCCPs are slipping through, other banned, restricted or disclosable substances could be as well. We don’t need a repeat of the 2007 “lead in toys” fiasco.

Visit DCA at www.DesignChainAssociates.com or email the author with any questions or comments on this post.

Follow TTI, Inc. on LinkedIn for more news and market insights.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed in posts by contributors are the responsibility of the authors alone and do not imply an opinion of the officers or the representatives of TTI, Inc. or the TTI Family of Specialists.